Breadfruit, engraving after a drawing by Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745 – 1771)

Eye-opening Records of Colliding Worlds

by Jonathan Jones,

for The Guardian

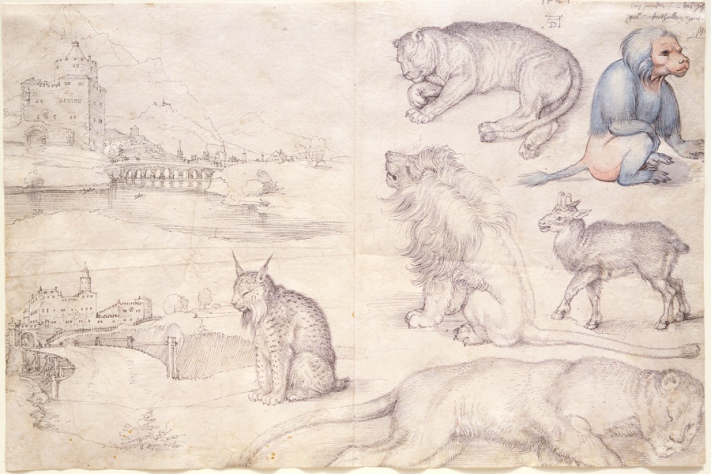

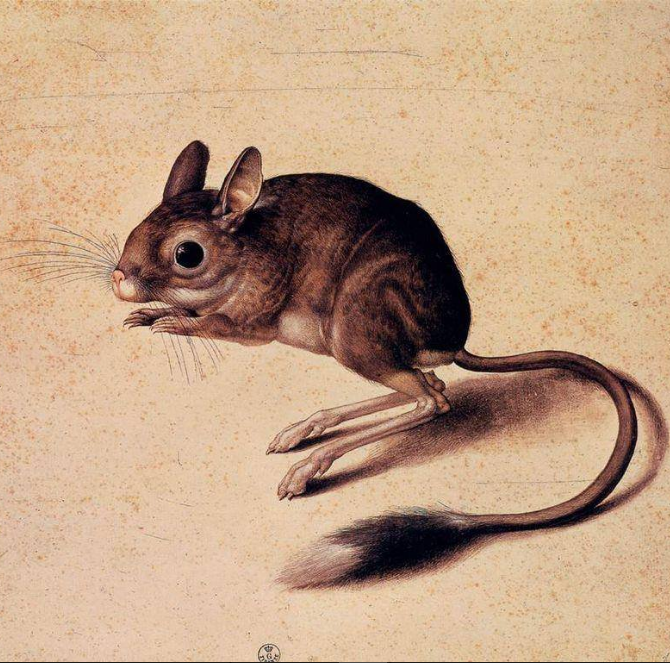

Sydney Parkinson drew the weird animal in a clear sharp line, looking at it carefully, then looking again, erasing his mistakes until he had an image that was beautifully recognisable. He wondered what to call this creature that was so utterly unlike anything back home in Britain.

He found out by speaking with local people and making a brief dictionary of their language. From a British Library exhibition: James Cook: The Voyages, a moving and absorbing account of a moment when worlds apart suddenly met –you can picture how they communicated by pointing at parts of their bodies: words like belly, hand, foot.

Among these basic terms is the name of the creature Parkinson drew. He transcribes it as “kangooroo”. It means, he says, “the leaping quadruped”. What he heard was probably the word “gangurru”, which is indeed the name of a type of kangaroo in the language of the Guugu Yimithirr people who James Cook, his crew, and the artists and scientists they took to the far side of the world met when they landed at the place they named Endeavour River.

As an attempt to give an Australian species an Indigenous Australian name, kangooroo isn’t bad. Parkinson’s drawing – the first ever made by a European – is just one of his sensitive scientific images of flora and fauna including a great white shark.

The adventure cost him his life: he died (of disease, not a shark bite) on the Endeavour’s voyage home. Another artist, Alexander Buchan, who portrayed the people of Tierra del Fuego, had died earlier in the voyage.

The fact that artists, as well as scientists such as the pioneering naturalist Joseph Banks, went on Cook’s voyages was unprecedented.

There were none on the ships of Columbus or Cabot. Cook’s first voyage went to Tahiti so a team of astronomers could observe the transit of Venus. They were not there to conquer. They got on well with the Tahitians – too well for Cook, who worried the newcomers would spread venereal disease and was upset when satirists back home had fun with the romantic exploits of Mr Banks.

Banks’s friendship with the Tahitian female chieftain Purea led to the most unexpected of the expedition’s artworks. Tupaia, high priest of the god of war, was part of Purea’s retinue. He not only became a translator for the English, but also started to record Tahitian life and beliefs in bold, compelling drawings. When the Endeavour sailed on to New Zealand he went too, and portrayed their encounters with Maori people.

Tupaia’s picture of Banks meeting a Maori, done in 1769, is one of the most eye-opening records of cultural encounter you could ever hope to see. For Tupaia, Banks and the Maori are foreign and fascinating. Banks in his blue coat is giving the New Zealander a piece of cloth in exchange for a big, red lobster. “I had a firm fist on the lobster,” remembered Banks. Tupaia also died on the Endeavour’s return to Britain.

Given the death rate of the Endeavour’s artists, it’s amazing that an up-and-coming painter, William Hodges, risked it all to go Cook’s second voyage. Not only would he survive, but he proved an accomplished, ambitious artist. His panoramic sketches of war canoes massing off Tahiti and a Polynesian vessel at sea are great works of art that anticipate JMW Turner – but Turner never went to the Pacific. His pictures of the Resolution and the Adventure isolated in the vast black seas of the Antarctic circle, menaced by towering icebergs, are even more daunting.

Suddenly, you see how far Cook sailed, how extreme the risks these 18th-century explorers took in their frail wooden ships. Hodges in Antarctica painted the most unearthly journey anyone had ever made.

His icy sketches are as incredible as images sent back today by the furthest space probes. But they were made by a human being shivering on a sailing ship with no radio, no contact with home, in a sea with no mercy. “We were the first that ever burst / Into that silent sea,” as Coleridge was to write in 1798, as if dreaming of these images by Hodges. Did Romanticism start in Antarctica?

An array of material at the British Library sets the remarkable artistic legacy of these voyages alongside a mass of documents from the original journals of Cook and Banks, the beautiful charts the captain made and to some of the first examples of Pacific art ever collected by Europeans.

By the end you feel dwarfed by the immensity of the world they sailed and haunted by the faces of the peoples they encountered. The violence of imperialism was coming. Yet this was a moment when strangers looked at one another with open eyes.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/apr/26/james-cook-the-voyages-british-library-review#comments

Order 3. Lepidoptera

Order 3. Lepidoptera Detail, Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Detail, Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream George Stubbs (1724 – 1806), Associate Member of the Royal Academy

George Stubbs (1724 – 1806), Associate Member of the Royal Academy