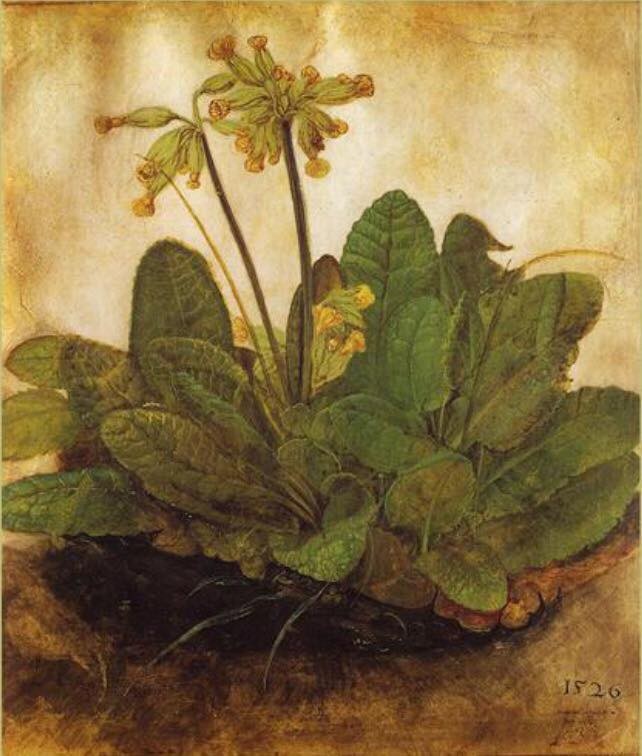

It seemed to me then that although we have fabulous compendia of flora, fauna and insects (Richard Mabey’s Flora Britannica and Mark Cocker’s Birds Britannica chief among them), we lack a Terra Britannica, as it were: a gathering of terms for the land and its weathers – terms used by crofters, fishermen, farmers, sailors, scientists, miners, climbers, soldiers, shepherds, poets, walkers and unrecorded others for whom particularised ways of describing place have been vital to everyday practice and perception. It seemed, too, that it might be worth assembling some of this terrifically fine-grained vocabulary – and releasing it back into imaginative circulation, as a way to rewild our language. I wanted to answer Norman MacCaig’s entreaty in his Luskentyre poem: “Scholars, I plead with you, / Where are your dictionaries of the wind … ?”

In the seven years after first reading the “Peat Glossary”, I sought out the users, keepers and makers of place words. In the Norfolk Fens I met Eric Wortley, a 98-year-old farmer who had worked his family farm throughout his long life, who had been twice to the East Anglian coast, once to Norwich and never to London, and whose speech was thick with Fenland dialect terms. I came to know the cartographer, artist and writer Tim Robinson, who has spent 40 years documenting the terrain of the west of Ireland: a region where, as he puts it, “the landscape … speaks Irish”. Robinson’s belief in the importance of “the language we breathe” as part of “our frontage onto the natural world” has been inspiring to me, as has his commitment to recording subtleties of usage and history in Irish place names, before they are lost forever: Scrios Buaile na bhFeadog, “the open tract of the pasture of the lapwings”; Eiscir, “a ridge of glacial deposits marking the course of a river that flowed under the ice of the last glaciation”.

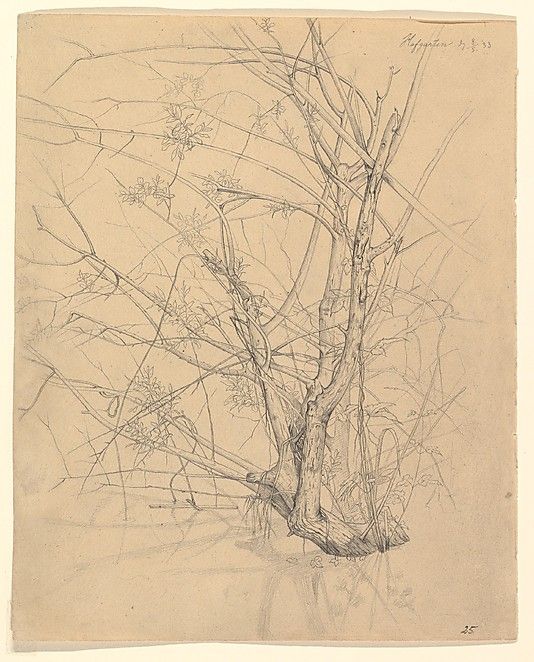

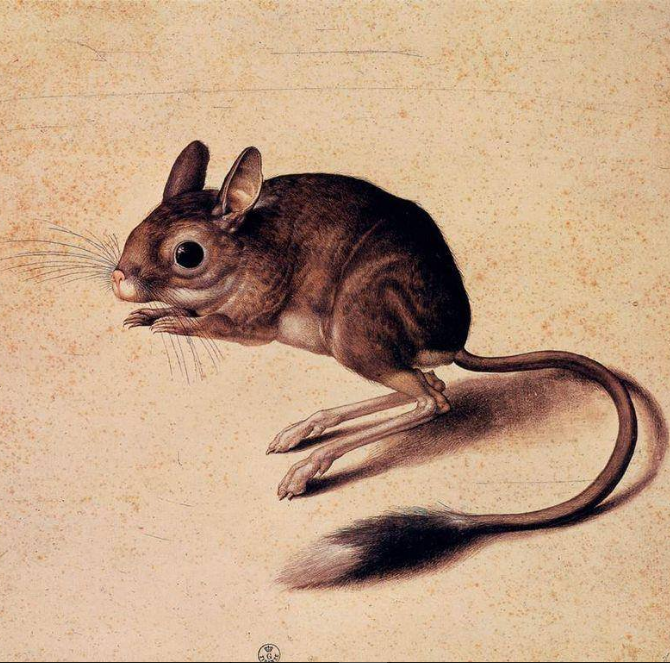

Some of the terms I collected mingle oddness and familiarity in the manner that Freud calls uncanny: peculiar in their particularity, but recognisable in that they name something conceivable, if not instantly locatable. Ammil is a Devon term for the thin film of ice that lacquers all leaves, twigs and grass blades when a freeze follows a partial thaw, and that in sunlight can cause a whole landscape to glitter. It is thought to derive from the Old English ammel, meaning “enamel”, and is an exquisitely exact word for a fugitive phenomenon I have several times seen, but never before named. Shetlandic has a word, pirr, meaning “a light breath of wind, such as will make a cat’s paw on the water”. On Exmoor, zwer is the onomatopoeic term for “the sound made by a covey of partridges taking flight”. Smeuse is an English dialect noun for “the gap in the base of a hedge made by the regular passage of a small animal”; now I know the word smeuse, I notice these signs of creaturely commute more often.

I also relished synonyms – especially those that bring new energy to familiar entities. The variant English terms for icicle – aquabob (Kent), clinkerbell and daggler (Hampshire), cancervell (Exmoor), ickle (Yorkshire), tankle (Durham) and shuckle (Cumbria) – form a tinkling poem of their own. In Northamptonshire and East Anglia “to thaw” is to ungive. The beauty of this variant surely has to do with the paradox of thaw figured as restraint or retention, and the wintry notion that cold, frost and snow might themselves be a form of gift – an addition to the landscape that will in time be subtracted by warmth.

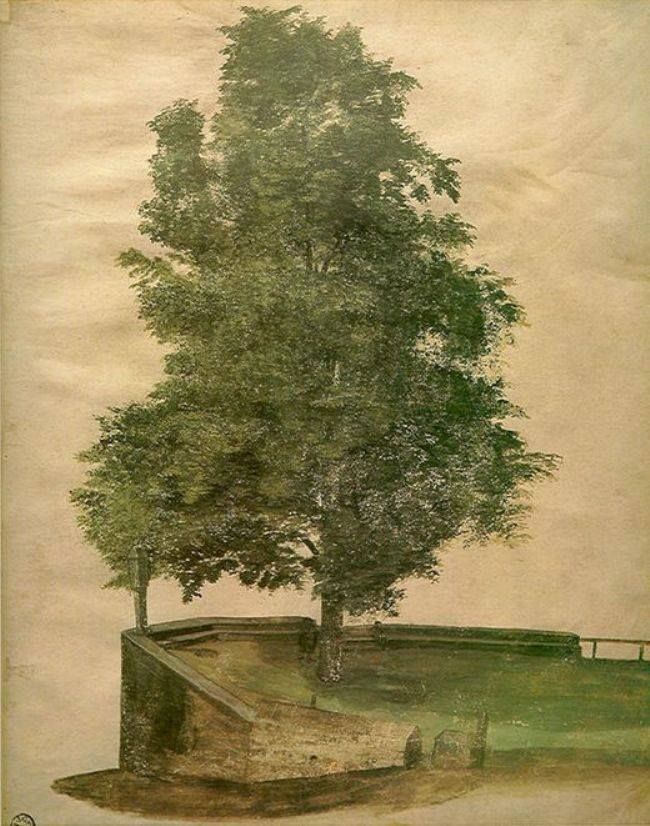

Many of the glossary words are, like ungive, memorably vivid. They function as topograms – tiny landscape poems, folded up inside verbs and nouns. I think of the Northamptonshire dialect verb to crizzle, for instance, a verb for the freezing of water that evokes the sound of a natural activity too slow for human hearing to detect (“And the white frost ’gins crizzle pond and brook”, wrote John Clare in 1821). When Gerard Manley Hopkins didn’t have a word for a natural phenomenon, he would simply – wonderfully – make one up: shivelight, for “the lances of sunshine that pierce the canopy of a wood”, or goldfoil for a sky lit by lightning in “zigzag dints and creasings”. Hopkins, like Clare, sought to forge a language that could register the participatory dramas of our relations with nature and landscape.

Not all place words are poetic or innocent, of course. Our familiar word forest designates not only a wooded region, but also an area of land set aside for hunting – as those who have walked through the treeless “forests” of Fisherfield and Corrour in Scotland will know. Forest – like many wood-words – is complicatedly tangled up in political histories of access and landownership. We inhabit a post-pastoral terrain, full of modification and compromise, and for this reason my glossaries began to fill up with “unnatural” language: terms from coastal sea defences (pillbox, bulwark, rock-armour), or soft estate, the Highways Agency term for those natural habitats that have developed along the verges of motorways and trunk roads.

I organised my growing word-hoard into nine glossaries, divided according to terrain-type: Flatlands, Uplands, Waterlands, Coastlands, Underlands, Northlands, Edgelands, Earthlands and Woodlands. The words came from dozens of languages, dialects, sub-dialects and specialist vocabularies: from Unst to the Lizard, from Pembrokeshire to Norfolk; from Norn and Old English, Anglo-Romani, Cornish, Welsh, Irish, Gaelic, Orcadian, Shetlandic and Doric, and numerous regional versions of English, through to Jérriais, the dialect of Norman still spoken on the island of Jersey.

It is clear that we increasingly make do with an impoverished language for landscape. A place literacy is leaving us. A language in common, a language of the commons, is declining. Nuance is evaporating from everyday usage, burned off by capital and apathy. The substitutions made in the Oxford Junior Dictionary – the outdoor and the natural being displaced by the indoor and the virtual – are a small but significant symptom of the simulated screen life many of us live. The terrain beyond the city fringe is chiefly understood in terms of large generic units (“field”, “hill”, “valley”, “wood”). It has become a blandscape. We are blasé, in the sense that Georg Simmel used that word in 1903, meaning “indifferent to the distinction between things”.

It matters because language deficit leads to attention deficit. As we deplete our ability to denote and figure particular aspects of our places, so our competence for understanding and imagining possible relationships with non-human nature is correspondingly depleted.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/27/robert-macfarlane-word-hoard-rewilding-landscape

Swearing Allegiance to The Particulars of the World

https://secretgardening.wordpress.com/2011/06/22/1154/

“Just as language has no longer anything in common with the thing it names, so the movements of most of the people who live in cities have lost their connexion with the earth; they hang, as it were, in the air, hover in all directions, and find no place where they can settle.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

A Windy Day

A Windy Day