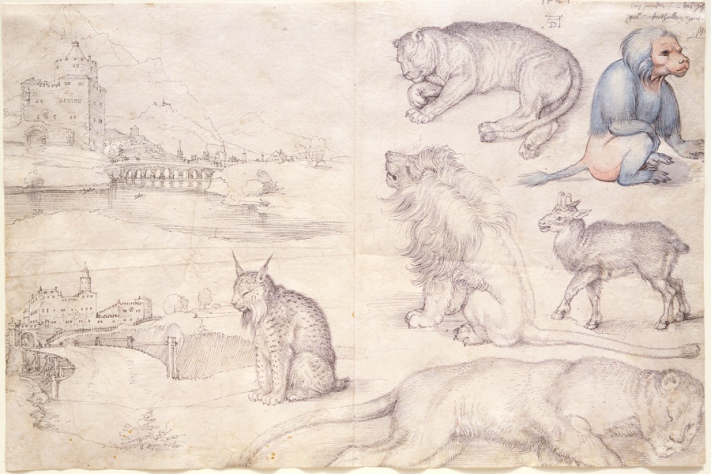

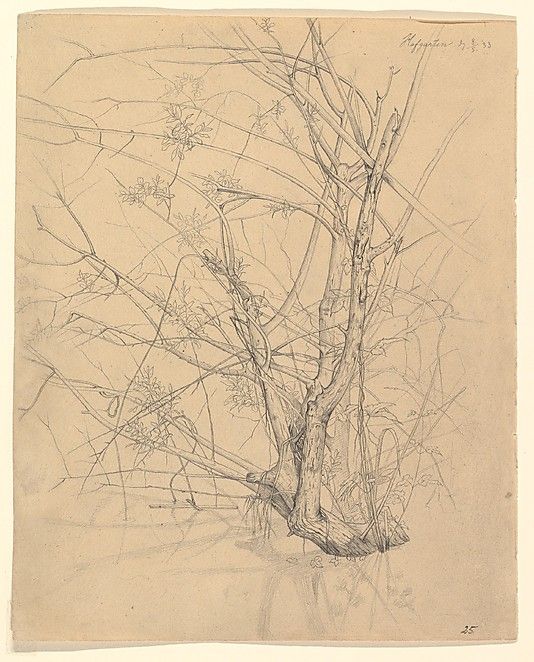

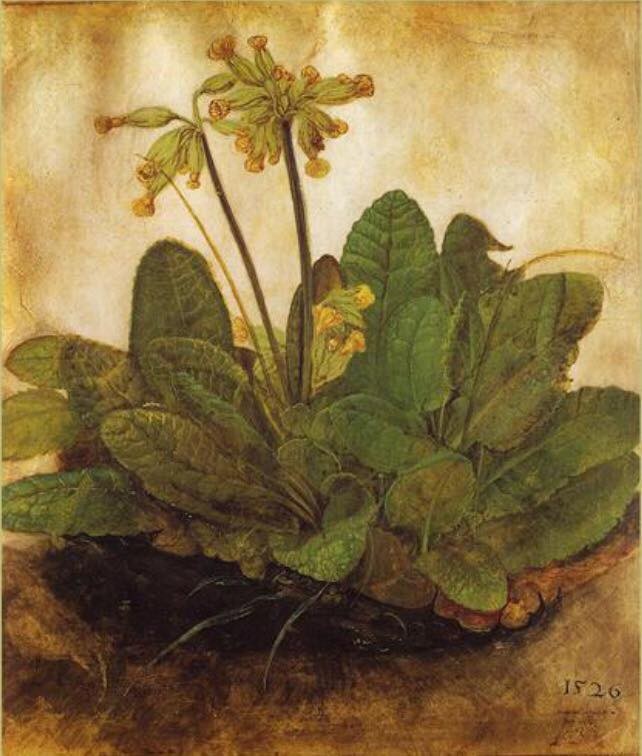

Hans Hoffmann (c.1530, Nuremberg – 1591/92, Prague)

Hans Hoffmann (c.1530, Nuremberg – 1591/92, Prague)

By Janusz R. Kowalczyk

Simona Kossak: they called her a witch, because she chatted with animals and owned a crow who stole gold.

She spent more than 30 years in a wooden hut in the Białowieża Forest, without electricity or access to running water.

A lynx slept in her bed, and a tamed boar lived under the same roof.

She was a scientist, an ecologist and the author of award-winning films and radio broadcasts.

She was also an activist who fought for the protection of Europe’s oldest forest.

Simona believed that one ought to live simply, and close to nature. Among animals she found what she could never find with humans.

“Simona first saw Dziedzinka in moonlight,” a relative remembers. “We decided we would go there at night time. The four of us went down the road with torches: my husband, a hired carter, myself, and Simona.

Suddenly, an aurochs stepped out onto the Browska Road. The horse jibbed, we got scared, but we got there.

Simona was enchanted with Dziedzinka straight away.” Years later, she described the expedition and the encounter with the king of the forest:

“It was the first aurochs that I ever saw in my life, I am not counting the ones in the zoo. And this greeting right at the entry into the forest – this monumental aurochs, the whiteness, the snow, the full moon, white everywhere, pretty, and the little hut hidden in the little clearing all covered with snow, an abandoned house that no one had lived in for two years. In the middle room, there were no floors, it was generally a ruin. And I looked at this house, all silvered by the moon as it was, romantic, and I said ‘it’s finished, it’s here or nowhere else!’”

Before Simona went to live in Dziedzinka, the house had to be renovated. The employees of the Białowieża National Park repaired the roof, changed the joists, got rid of the fungus, and said that that ought to suffice for five years (and indeed it did).

After the renovations, Simona did her part. She papered the walls, washed the windows, added a bench, and upholstered the armchairs that were brought from her family home.

She brought clocks, as well as a Turkish dagger, lace tablecloth and window curtains, books, oil lamps, an antique iron, a collection of weapons, ebony jewellery chests, as well as glassware, porcelain, cupboards and an oak bed.

She hung a shotgun from the Kossaks’ collection right by the door. A large tile stove in the old style stood in the corner of the room, and a large table in the middle – her workshop and study, where she worked by an oil lamp.

Simona rode a motorbike, sometimes a tractor, and she also swept through the landscape on cross-country skis.

A hunter recalled, “Once I saw this phenomenon advancing on a komar – wind in the hair, a pilot-cap, rabbit pants, and eye goggles. It passed me by and I had to turn around, because I didn’t know what it was”.

Professor Kajetan Perzowski, a colleague of Simona’s from her university years in Kraków says, “We were once going across the Białowieża Forest with a friend in a small truck. We suddenly see someone pushing through the snowdrifts carrying a motorbike on the back. It was Simona. We packed her together with this motorbike onto our truck. She made us a big pot of stew at Dziedzinka.”

The forester of Białowieża National Park, Lech Wilczek, was her housemate, and one day brought home a newborn wild boar piglet. The humans grew close to each other, and the female boar, eventually immense, lived with them for 17 years.

“She stood vigilantly at the door like a dog, she went out on walks, and more and more often she cuddled up to her people and demanded to be caressed.”

The crow. He stole cigarette cases, hair brushes, scissors, and the lumberjacks’ sausages. He tore up bicycle seats and made holes in grocery bags.

Said a forest worker, “He would even steal the workers’ pay. But once I was walking around the reserve without a permit, and the guard saw me and started to fill in a penalty slip. While he was handing it to me, the crow appeared. He took the paper in his beak, flew to the roof of Dziedzinka, and tore it up with his leg. The guard didn’t know what to do, and finally just shrugged his shoulders at the whole thing.”

“He loved to attack people who rode bicycles, especially girls. It was very impressive, he would attack the rider’s head with his beak, the person would fall off, and he then would perch on the seat triumphantly, looking at the spinning wheel.”

People thought that Korasek – because that’s what he was called – was some kind of a punishment for their sins.

Simona’s friend: “Once he stole my car keys. And Lech said “Don’t worry, he’ll bring them back.” He told the bird that if he returned the keys he would get an egg, and if he didin’t he would be punished. And the crow perhaps understood this, because after a moment, he flew up to me, furious, with the keys in his beak and threw them onto a table!”

With time, more animals appeared: a doe who approached the window and ate sugar, a black stork for whom Simona created a nest in a drawer, a dachshund and a female lynx who slept in Simona’s bed, and peacocks. She loved, healed, and observed them all, while Wilczek photographed them. Here, as a mother she raised moose twins, Pepsi and Cola, washed the neck of the black stork, kept the female rat Kanalia in her sleeve (as the animal panicked in open spaces). She would let the befriended doe give birth on the patio, took in lambs with their mother, and sheltered the rats Alfa and Omega. She checked on weather by observing bats in the basement.

The menagerie grew with each year.

Simona raised several deer by bottle-feeding orphaned fawns, and followed them around the woods for many years.

“One day, my pack of deer showed signs of fright, and did not want to go out onto the forest field to graze. And I started to approach the young forest, because this was the direction in which the deer startled, their ears raised, and the hair standing up on their rumps: apparently something very threatening was in the woods.

I crossed about half of this open space, but I stopped, because I heard a choir of terrified barking behind me. When I turned around, what I saw was five of my deer standing stiffly on tense legs, looking at me, and calling with this bark: don’t go there, don’t go there, there’s death over there!

I must admit, I was dumbstruck, and then finally I did go. And what did I find? It turned out that there were fresh traces of a lynx that had crossed the young forest. I went in deeper, and I found lynx droppings, still warm.

What did that mean? It meant that a carnivore had approached the farm, the deer noticed, were frightened and ran, and then what did they see?

They saw their mother going toward death, completely unaware, and knew she had to be warned. And for me, I will honestly admit, this day was a breakthrough. I crossed the border that divides the human world from that of the animals. If there was an impermeable barrier, they would not have taken action–they would probably not have noticed what I was preparing to do. That they noticed, anticipated what might happen to me, and responded, meant one thing and one thing only: you are a member of our pack, we don’t want you to get hurt.

I admit that I relived this event in my mind for many days, and in fact today, when I think about it, my heart warms.”

In the winter of 1993, Simona commenced her war to save the lynxes and wolves of Białowieża.

A group of scientists planned to collar the animals for data-collection, but Simona came across traps in the form of metal jaws, so she took them with her and refused to give them back.

There was a hearing during which she pointed out that there were 12 lowland lynxes left, in danger of being poached—and now in danger of being mortally wounded by the traps.

“It is a disgrace for the world of science to have contributed to this.”

[Now the entire Białowieża Forest, which includes some of Europe’s last primeval woodland, is under threat.

Białowieża was designated a Unesco World Heritage site in 1979, but Poland’s environment minister, who has allowed large-scale logging for years, has called for the woodland to be stripped of Unesco’s natural heritage status.

The forest is–for now–home to 20,000 animal species, including 250 types of bird and hundreds of European bison, plus firs towering 50 metres (160ft) high and old oaks and ashes.]

http://culture.pl/en/article/the-extraordinary-life-of-simona-kossak

[wonderful photographs of Simona Kossak and her menagerie at Dziedzinka in the Białowieża Forest,]

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/25/poland-starts-logging-primeval-bialowieza-forest-despite-protests

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/22/primeval-forest-bialowieza-must-lose-unesco-protection-says-poland

http://www.poranny.pl/magazyn/art/5423022,simona-kossak-puszcza-bialowieska-i-lech-wilczek-dziedzinka-stala-sie-ich-domem,id,t.html

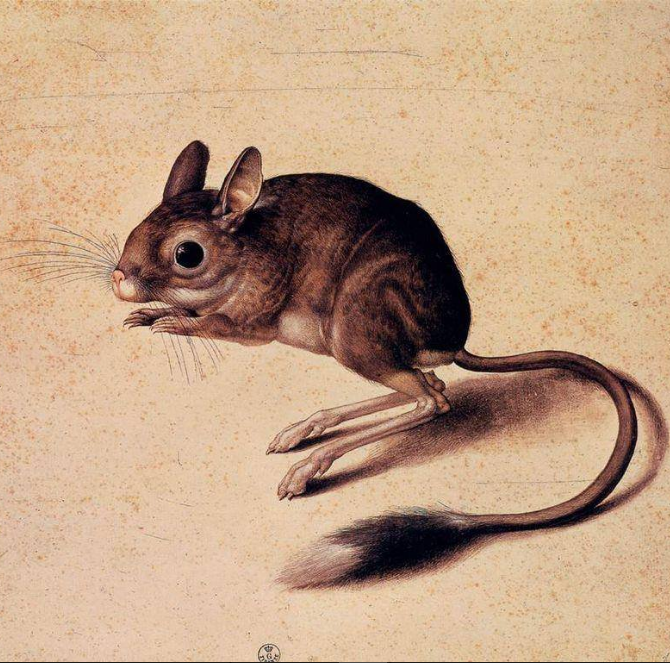

Jacopo Ligozzi (1547, Verona–1627, Florence)

Jacopo Ligozzi (1547, Verona–1627, Florence) Hans Hoffmann (c.1530,

Hans Hoffmann (c.1530,

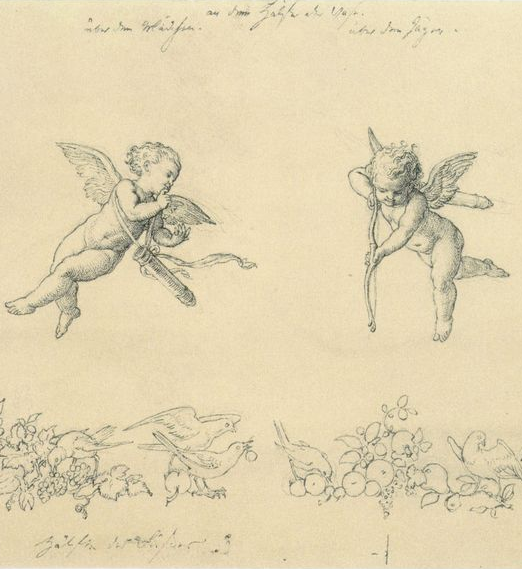

Václav Hollar (1607 – 1677)

Václav Hollar (1607 – 1677)

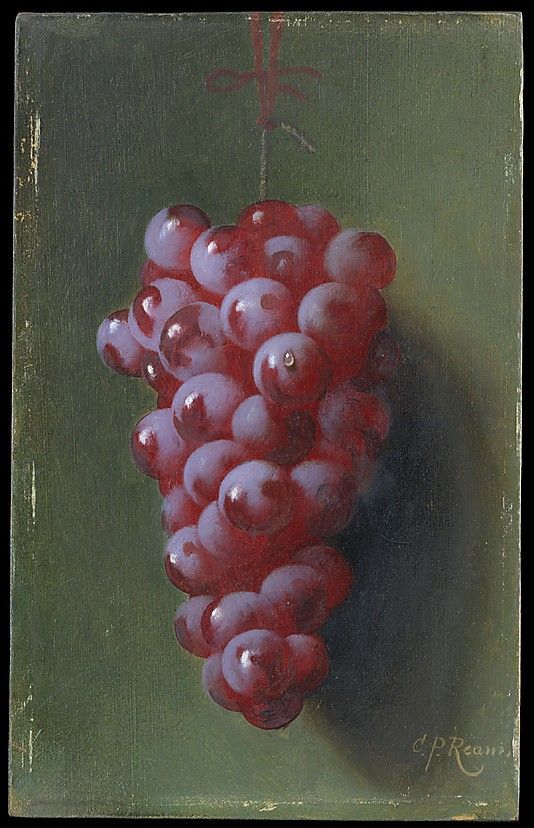

Georg Flegel (1566 Olomuc-23 March 1638

Georg Flegel (1566 Olomuc-23 March 1638  John La Farge (March 31, 1835 – November 14, 1910)

John La Farge (March 31, 1835 – November 14, 1910) Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (1844 -1916) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (1844 -1916) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania