Abbott Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849 – May 29, 1921)

Abbott Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849 – May 29, 1921)

“Less Thing-Like”

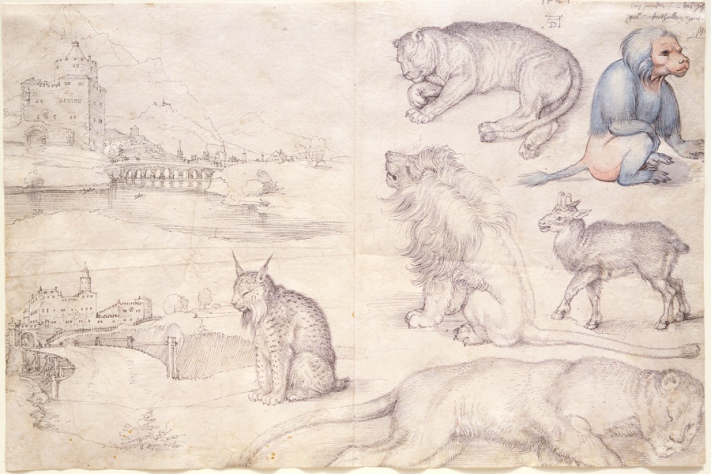

Abbott Thayer was a lifelong wildlife advocate whose artistic focus never strayed far from his personal fascination with the natural world.

On 11 November 1896 he made an appearance at the Annual Meeting of the American Ornithologists’ Union in Cambridge, Massachusetts arriving at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology on Oxford Street bearing a sack of sweet potatoes, oil paints, paintbrushes, a roll of wire, and two new principles of invisibility in nature that together formed his “Law Which Underlies Protective Coloration.”

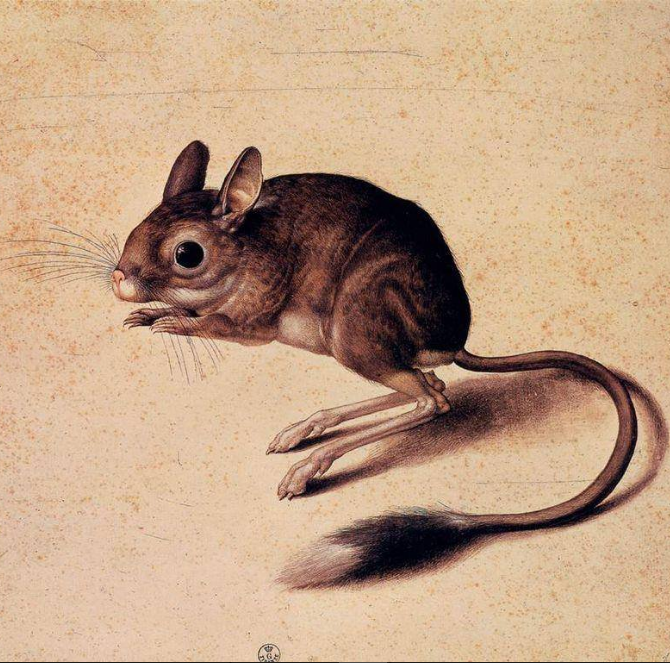

In his afternoon open-air lecture, Thayer argued that every non-human animal is cloaked in an outfit that has evolved to obliterate visual signs of that animal’s presence in its typical habitat at the “crucial moment” of its utmost vulnerability.

Thayer arrived at camouflage inadvertently, in the process of pursuing art.

As a student, he had learned that any shape drawn on a flat surface can be given volume and dimension by a venerable process called shading. This is reliably achieved by rendering the shape lighter on the top and gradually darker toward the bottom.

As we know from current brain research, this takes advantage of an inborn visual tendency called the top-down lighting bias: when we look at anything, we default to the assumption that its light source is coming from overhead.

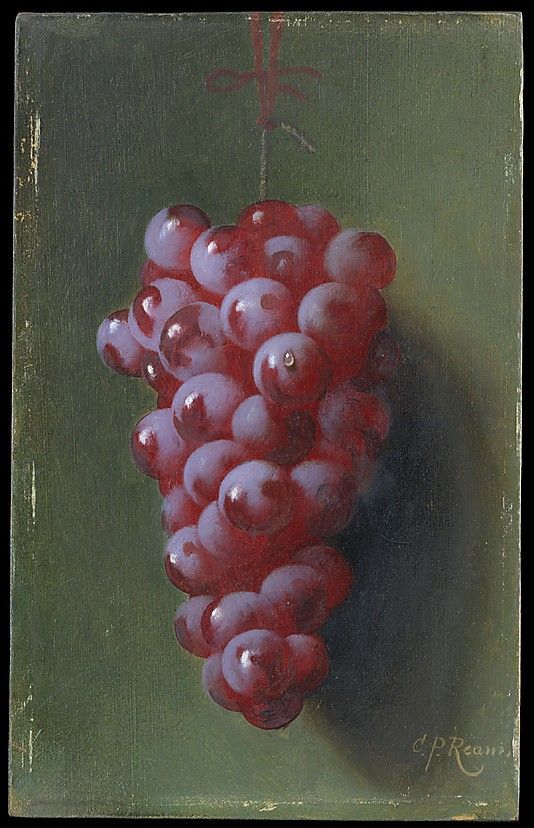

Observation then enabled him to realize why so many animals have light colored bellies with darker coloring toward the tops of their bodies. The effect is the inverse of shading.

Appropriately, it became known as countershading, because the effect counteracts the shadows resulting from cast sunlight, making an animal look less dimensional, less solid, less “thing-like.”

Though some of Thayer’s other proposals have been disregarded, countershading is a widely accepted biological principle today, and stands as the artist’s most significant contribution to the natural sciences.

By 1896, Thayer was increasingly inserting himself into what was a longstanding debate over the origins, effectiveness, and pervasiveness of protective concealment in the natural world.

After the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859, animal coloration—both its origins and its role in animal behavior—had become a key locus of debate among natural historians, artists, and the lay public.

Prior to this period, naturalists had noted instances of animals’ blending in with their backgrounds. It seemed remarkable that God had “dropped” them into place just so—“nature by design.”

By contrast, in an evolutionary model, there was a gradual “fitting together” over time. Evolutionary theories, both Darwin’s and that of his colleague Alfred Russel Wallace, presented a range of explanations for animal colors. Darwin emphasized interrelations between the sexes as the cause of the showy coloration found in the male of many species; females chose the more colorful males for mating.

Wallace, studying the colors of many insects, interpreted bright hues and complex patterns alike as either warning signals to potential predators, modes for assimilation in the environment, or mimicry of other, more dangerous, species.

Meanwhile, philosopher-psychologist William James, a friend of Thayer’s and a fellow birder, discussed the experience of bird watching in his 1890 Principles of Psychology, describing the study of illusions, or so-called “false perceptions,” as critical in efforts to understand human apprehension of depth, color, and movement.

Thayer’s New Hampshire summer home, to which he and his family relocated around 1900, was transformed into a year-round laboratory for studying protective coloration.

His communion with nature permeated the entire household. Wild animals—owls, rabbits, woodchucks, weasels—roamed the house at will. There were pet prairie dogs named Napoleon and Josephine, a red, blue and yellow macaw, and spider monkeys

Soon, his wife Emma, son Gerald, and daughters Mary and Gladys joined him as fellow investigators, technicians, and artisans.

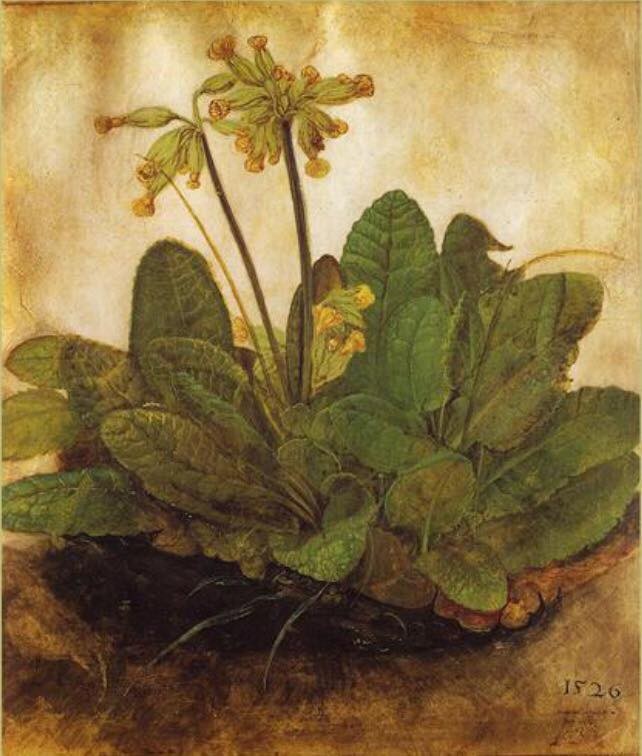

Between 1901 and 1909, their generative theories were built up into a universe of paintings, photography (a new technology), collages, stencils, and essays. Each format addressed the enigmas of coloration and invisibility in different ways.

Thayer was simultaneously producing, witnessing, and documenting the processes of a living being’s assimilation into its habitat.

A wonderful marriage of science and art. Thanks for this post – I learned a lot.

I learned a lot! And there’s more. I posted a landscape of his once–And next time I’d like to tell more about his vision, in both senses of the word (and senses)

love this

Hi! Thank you; It turns out that he’s pretty loveable.

Art lessons taught by nature – the best techniques and most interesting subjects.

Which would account for virtually all of it—but this time, the funny part was the lesson taught by art to naturalists (and later to makers of protective garb for humans)

—My favorite artists are certainly those most attentive to nature.

I do find the whole subject fascinating, in spite of not being an artist—which I have rued my whole life—

Rue no longer – start to paint. Never too late.

It is a complete mystery to me.

I don’t mind drawing badly & experimenting with an always differently executed wash of watercolor over the drawing–But applying paint to build an image is something my mind simply can’t grasp. I can only admire—-

But thank you for the encouragement, which I will take as a boost in general—